Alabama Child Custody and Divorce Trials

Even after you've opened your custody or divorce case, you can keep trying to settle with the other parent. Reaching agreement on all issues means you won't need a trial. You'll submit your parenting agreement to the judge to turn it into a court order. However, if you have open issues that need to be decided by a judge, you'll head to trial.

Each Alabama county has its own court procedures, so you may encounter different forms and deadlines. Your trial could be virtual.

Trying to settle

Mediation resolves most cases, so it's usually worth a try. Legal professionals recommend it unless your case involves abuse.

In the northwest part of the state (e.g., Lauderdale, Limestone, Colbert, Lawrence, Morgan and Cullman counties), the judge often orders parents to try mediation — and to provide proof that they went — before they schedule a trial.

In Birmingham, judges sometimes order mediation, but it isn't automatically required for everyone.

Timing of a trial

After opening a case, if you've decided you'll need the judge to resolve your dispute, start gathering evidence and then submit a petition for a trial date. Ask the court clerk for the right form.

Each court has its own timing for scheduling you. The courts are busy, so you may have to wait a while to find out the date, and the date you receive may be for weeks or months in the future.

Your local judge might require all parents to attend certain hearings before trial, like one to address readiness for trial. Or they might ask you to come to a hearing to address an issue specific to your case. The hearings could be virtual.

Parents who head to trial can expect their case to last at least six months. It may last a year or more.

If you need to postpone your trial, submit a Request to Continue Trial. You must give a reason.

Preparing for trial

At trial, the judge will determine what custody arrangement best supports your child's needs.

Be ready to show how you'll emotionally support and materially provide for your child and how you'll help maintain their relationship (if appropriate) with the other parent.

Discovery

Through a process called discovery, you may request information from each other. You and the other parent may send in writing:

- Open-ended questions. You can ask up to 40 questions about the other parent's personal situation, parenting approaches, home environment, and so on. These questions are called interrogatories.

- Requests for admission. The other parent must respond to a statement with "admit" or "deny." If they don't deny it, Alabama considers them to have admitted to it.

- Requests for documents. You can request documents like financial statements.

- Requests for spoken testimony. You can ask the other parent to testify for up to seven hours while a court reporter transcribes their responses. It's called deposition.

Each parent must comply with the other's requests that meet the rules for discovery.

Evidence

With the information you've gathered through discovery and other means, prepare a thorough, clear argument.

Plan for whether you'll call witnesses at trial. There isn't an official limit on how many you can call, though the judge can place limits so the trial isn't unreasonably long.

If you have other supporting information — for example, a photograph, bank statement or proposed parenting plan — you can use it as a trial exhibit.

File a list of witnesses and exhibits with the court, and serve a copy to the other parent. Check local rules, and use your courthouse's forms. For example, in Morgan County, you must provide a description of your exhibits 14 days before trial, and any update to the list seven days before trial.

If you miss the deadline, your witnesses probably won't be allowed to testify, and your evidence won't be considered an exhibit. You can still bring documents to the courtroom and look at them while you're verbally testifying. The judge may agree to look at them but can't give them as much weight as they would give to formal exhibits.

What happens in court

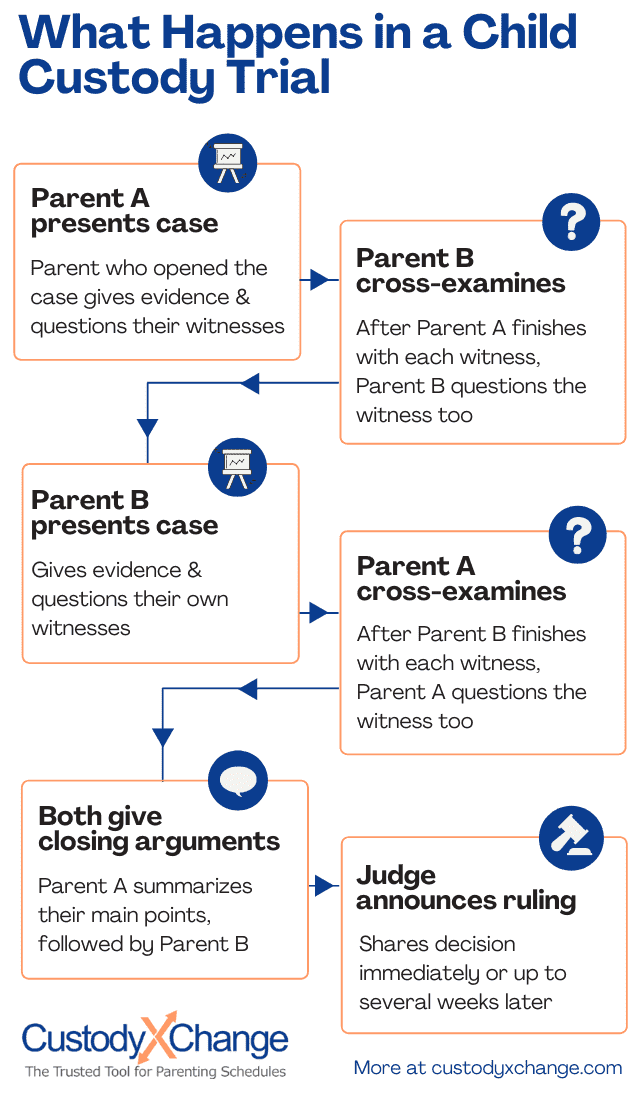

Trials are open to the public unless the judge finds a reason to make them private. The exact order of the proceedings is up to the judge. There's no jury.

The judge may allow both parents to make an opening statement. If you want to do this, ask permission, and keep your statement brief.

The plaintiff (the parent who opened the case) argues by presenting evidence and calling witnesses. The defendant can question (cross-examine) the plaintiff's witnesses, e.g., to challenge the consistency of what they've said.

Next, it's the defendant's turn to present evidence and call witnesses, and the plaintiff cross-examines them.

At the end, each parent may have an opportunity to make a closing statement. Again, ask permission, and keep it brief.

Reaching a decision

After reviewing the evidence and listening to the arguments, the judge determines what custody arrangement is best for the child. You'll probably leave the courthouse without knowing your outcome, as the judge will need a few days or weeks to think about it and to write the order.

The judge considers the ability of each parent to comply with the arrangement (e.g., your health, incomes, work schedules and transportation).

The judge is also allowed to consider a parent's "character." For example, if one of you has been unfaithful to the other, the judge can use that information when deciding child custody — even if you're not fighting over it or citing it as a ground for divorce.

If you believe the judge made a glaring error and their decision really doesn't make sense based on the evidence, you can appeal the decision to another court.

If you simply disagree with the order, you can ask to change the order in the future, especially if doing so is necessary to meet the child's needs. Changing an order is much easier when you and your co-parent agree. Otherwise, you'll have to repeat much of the court process.

If a guardian ad litem is involved

A guardian ad litem represents the child's best interests. To do so, they learn about the child's family situation and personal needs. If you disagree with their findings, you can request a hearing.

The court may appoint a guardian ad litem when paternity is disputed or when the child's physical safety or financial savings are at risk. You may ask for a guardian ad litem, but their role only begins when the court appoints them.

Their role in your case could be as a lawyer (who can call witnesses at trial) or as a witness (who can testify at trial), but not both.

If your child already has a guardian ad litem in one court system, the guardian may not automatically transfer over to another court system. For example, a guardian ad litem serving your child in juvenile court may not be able to continue serving them in your divorce proceedings in circuit court.

Using technology for your trial

Going to trial over child custody requires serious organization.

You'll need to present evidence, which could range from messages with the other parent to a calendar showing when you care for your child. You should also present a proposed parenting plan and schedule to the court.

The Custody X Change app lets you create and manage all of these elements in one place.

With parent-to-parent messaging, personalized custody calendars, a parenting plan template and more, Custody X Change makes sure you're prepared not only for trial but for every step of your case.

Take advantage of custody technology to get what's best for your child.